Tags

awesome, interviews, minneapolis, present day, real life, research

08 Monday Jul 2013

Posted in Present Day, Real Life

Tags

awesome, interviews, minneapolis, present day, real life, research

27 Thursday Jun 2013

Posted in Kenny Institute, Society

Tags

“‘Bill’ Stanley William / Willis Bell (??)”

That name is written not far beneath Elizabeth Kenny’s, in my roster of important figures in this absurdly crowded story. So far, I’ve talked only about Kenny herself, and about her patients—and, in my last post, about myself—but there are dozens, if not hundreds, of others who figure into this story. They are nearly as vibrant and dynamic as its central character, but were afforded nowhere near as much press coverage, and finding ways to get to know them has proven both delightful and infuriating.

This story is vast, almost beyond my ability to see it all at once, force a wide and ever-changing vista into a single frame. It’s yet another part of what I love about it: its enormity, and the delight I take in the knowledge that each one of the many thousands of people who passed through the Kenny Institute, for a week or a month or a year, came away with a different impression of what the place was and exactly who the people were that lived and worked there.

Because it’s not what a thing really is that we see, that we remember. It’s what it means to us.

The physical therapist with that heavily annotated name is one of my favorites: one of the most interesting, and so far one of the most enigmatic. It isn’t just that the names on his paperwork don’t match up (though they don’t, always, with William/Willis the main point of contention). It’s that he seems to have used different names with different people—and it’s that one small quirk that has me curiously transfixed.

It was while I was talking to my interviewee Russell, who fell ill in the summer of 1940, that I figured this out: I’d asked him about the people who cared for him other than Kenny, hoping to draw out some of the names I already knew. “[S]he had one male and one female nurse that was on her staff, Australians,” he said, but he couldn’t remember their names.

The girl was probably Mary, I told him, or else Valerie: Kenny’s adopted daughter and protégé, and her favorite physical therapist, respectively, both of whom accompanied her from Australia. The boy’s name was almost certainly Bill, another therapist she’d trained—someone I’d heard stories about, who all of the kids seemed to adore. I’d read a lot about Bill, and I was confident that this was Russell’s guy. Did any of that sound familiar? I asked.

It didn’t. Not then. But a few minutes later, he told me about this “orderly” he’d worked with almost constantly, someone who helped him with his treatments and carried out his exercises. Stan, he said, thoughtlessly. Sliding out, the way things do, from dark corners of memory too cluttered to retrieve anything from when you rifle through them in the light.

And something went off in my head.

Stan. Stanley? Stanley William? Bill?

I’d read people’s recollections about the somewhat unfortunately named Bill Bell, but never any—at least, none that I recall—about Stan. And yet it’s obvious that the man Russell spoke of with such mischievous warmth in his voice was the same one who’d watched over so many others in their most fragile and brilliant moments: outgoing and deadpan and subversively indulgent, with the same Aussie drawl Kenny had.

Stanley et cetera Bell was one of the Kenny Institute’s first staff members—he started working for Kenny in the States in 1940, and the Institute wasn’t dedicated until December of 1942—and to all appearances one of its most beloved. Kenny summoned him from Australia the instant she was ensconced in Minneapolis; she had trained him in physical therapy at a clinic she ran in Queensland, and the two had worked closely together for his entire career to date. As apparently skilled and authoritative as anyone else on Kenny’s staff, Bill/Stan also had a bit of a “good cop” reputation, contrasting with the women’s more severely expressed expectations. “Stan and I got along like a million bucks,” Russell told me, grinning, and it was clear that to a lost, lonely kid looking for guidance, that meant everything.

The Kenny Institute, as it was in the 1940s, was, and still sometimes is, accused of being a “cult of personality”—but no hospital serving nearly a hundred people as long-term inpatients, and two or three times that during certain epidemic swells, could operate on the strength of a single individual, no matter how formidable she might have been. Sister Kenny’s ethos permeated the place, but it’s the auxiliary staff former patients recall most vividly: the people they saw every day, sometimes more than once. (Sometimes an exasperatingly large number of times.) The nurses. The “packers” who swathed their bodies in hot wool blankets to ease their cramps. And the therapists, who coaxed them so slowly and steadily back to life. People who knew them better than they knew themselves, at least for that brief breath-held moment in time, who bore witness to their tears and shared in their triumphs, and were both the cause and the cure of their pain.

The Kenny Institute, as it was in the 1940s, was, and still sometimes is, accused of being a “cult of personality”—but no hospital serving nearly a hundred people as long-term inpatients, and two or three times that during certain epidemic swells, could operate on the strength of a single individual, no matter how formidable she might have been. Sister Kenny’s ethos permeated the place, but it’s the auxiliary staff former patients recall most vividly: the people they saw every day, sometimes more than once. (Sometimes an exasperatingly large number of times.) The nurses. The “packers” who swathed their bodies in hot wool blankets to ease their cramps. And the therapists, who coaxed them so slowly and steadily back to life. People who knew them better than they knew themselves, at least for that brief breath-held moment in time, who bore witness to their tears and shared in their triumphs, and were both the cause and the cure of their pain.

It was the most intimate relationship many of them had ever had—not just the children, but, by all accounts, many of the adults as well. It amazes me how openly Kenny patients talk about their doctors and therapists—not just in retrospect, but in things they wrote while they were still in the hospital, or shortly thereafter. They seem to have talked to them just as candidly: without any of the frightened reverence I’m used to seeing in the face of such an authority gap, they tease and question them even as they look to them for guidance. It’s respect, and well-earned, not intimidation.

It’s like I wrote in the last post: this is real life. With all of the extraneous distraction, and all of the social nicety, stripped away. If you didn’t have the luxury of hiding from it, it was good at least to have someone with whom to share, and these were the people they could trust. And the patients—some of them, anyway, when they were ready—plunged into this highly unusual dynamic with an abandon and a sense of freedom they didn’t seem to feel anywhere else. You weren’t supposed to talk about it—about polio, about your fears, about much of anything at all; recollections of interactions with family and friends frequently emanate squirming discomfort. But this specific relationship, between the Kenny patients and their therapists, that you might expect to be so fraught with expectation and fear, is both ocean-deep and light as air.

And they entrance me, coming to life on these old and crinkled pages. It’s uncanny, in a way, to come away with such a strong impression of an individual—not just the mysterious Mr. Bell, but so many of these people, the ones who show up all the time and the ones I’ve “met” just once or twice—without actually knowing anything about them. I have a copy of a card with Bell’s credentials on it—but most of Kenny’s resume was faked, so I have a hard time believing his is wholly straightforward. He spent some time in the military starting in 1945, but how that came about, and why, as far as I can tell, he never returned to the Institute, remains a mystery. He was married, with at least two children, but I don’t know anything about his family besides that they existed.

The only thing about Bill/Stan Bell I don’t have any trouble figuring out is why he was so thoroughly beloved. The first story I ever read about him was relayed by a man named Robert Gurney, in an interview for the book Polio’s Legacy. Robert called him Bill. He called him Bill, and he spoke about the winter of 1940, and learning to walk again: seventeen years old at the time, Robert insisted he couldn’t do it, but his technician felt otherwise. After a couple unsteady laps around the therapy table, Bill announced that Robert, with Bill’s help, was going to walk back to his room. This plan seemed difficult to protest, so off they went, until one of Robert’s friends noticed him walking alone and called out congratulations; as it turned out, Bill had stopped to “[talk] to a couple of pretty nurses,” and Robert had inadvertently kept going without him. As soon as he realized what had happened, Robert promptly wavered and fell, but he tells it as a deeply happy story, infused with nostalgia, tinged with gratitude.

The only thing about Bill/Stan Bell I don’t have any trouble figuring out is why he was so thoroughly beloved. The first story I ever read about him was relayed by a man named Robert Gurney, in an interview for the book Polio’s Legacy. Robert called him Bill. He called him Bill, and he spoke about the winter of 1940, and learning to walk again: seventeen years old at the time, Robert insisted he couldn’t do it, but his technician felt otherwise. After a couple unsteady laps around the therapy table, Bill announced that Robert, with Bill’s help, was going to walk back to his room. This plan seemed difficult to protest, so off they went, until one of Robert’s friends noticed him walking alone and called out congratulations; as it turned out, Bill had stopped to “[talk] to a couple of pretty nurses,” and Robert had inadvertently kept going without him. As soon as he realized what had happened, Robert promptly wavered and fell, but he tells it as a deeply happy story, infused with nostalgia, tinged with gratitude.

“Henry [the friend] was laughing so hard he was crying,” Gurney says, “and I was just sitting on the floor laughing. But from then on, I walked.”

The interview is eight or nine pages long, and only one of them deals with this incident, much less Bill himself. But I came away from those bare sentences with a distinct impression of who this person was and how he thought (though I still can’t decide whether the detour to chat up the nurses was an actual lark or just a ruse). I feel like that’s the opposite of what usually happens, like I’m getting to know these people inside out: it’s so easy to accumulate semantic details about a person—what do you do, where are you from, where’d you go to school?—and so hard to actually learn anything about who they are. But these people come across as so raw, so earnest, so inside-out, that it’s hard not to see them right away. You see them in their letters, in their memos, in the stories that others tell about them, so enthusiastic and conspiratorial: the way they really were, in the day-in and day-out of a job both unforgiving and unfathomably rewarding.

That’s why I’m so curious about the name change. About why Russell talks about Stan, and Robert reminisces about Bill, when they met him the very same summer, a span of time in which you expect there to be a united front. Maybe it’s an odd thing to have latched onto so tightly, and with such insistent curiosity. But names have a literally mythological power, and changing them is more than just semantic, because your name tells you—you, not just the rest of the world—so very much about who you are. You can be a different person, with a different name. Even if they both belong to you, and neither one is a “disguise.”

I know because I changed my name, a little less than a year ago, one little piecemeal introduction at a time, from something that merely belonged to me to something that was mine. I’d been Tori since I was born, an abbreviation of a given name I claimed to hate, and that even my parents never meant to call me aloud: too regal, too stuffy. I was so stubborn about it that it says Tori on my university diploma. But about a year ago, with the world swirling around me, I started wondering if that was the person I felt like—or the person I wanted to be. I started wondering about Tori on the cover of a book. And then, one day, with a small and instantaneous thrill of transgression: Hi. I’m Victoria.

I love this “new” name. Victoria is who I chose to be. And there are many people in my life now who know me only that way: when my yoga teacher Matt calls me out in class, it is Victoria he gently chides; Victoria is the name at the top of this page. It startles me when I swipe my loyalty card at the chain café I’ve eaten at practically every other day since I was a teenager, and when my order comes up they call out, “Tori?” And yet, sometimes, for reasons I can’t even fathom, a department store salesperson will ask my name, and I’ll chirp the shorter version—not because I forget, for a moment, but because it feels more appropriate. Even though most of the time I cringe, unfairly, when I see that worn-out word, the old name, a relic of a person I’m relieved to no longer be.

Sometimes a name is just a name. But sometimes it’s a threshold.

So that’s a moment—a pair of them, in fact—I wish I somehow could have witnessed: whatever the space was between Stan/Bill’s two introductions, and whatever spontaneous impulse triggered the change. Maybe different people seemed to need different things. Maybe different contexts brought different levels of comfort. Maybe he was still trying to figure out who he was going to be in the U.S., and whether that was any different from the person he had been back in Australia. Maybe it’s nothing. Maybe he went by both names as a matter of course, and the kids he worked with picked their favorite as shorthand. Maybe one of the boys whose stories I’ve mentioned couldn’t remember at all, and paperwork or an interested family member supplied a name different from the one he used every day. Or maybe there was somebody else named Bill, or Stan, on one of those wards, and that someone was unusually protective of his name.

I probably won’t ever know. Not that particular detail, so specific, and so likely inconsequential, no matter how much I want to read into it. I’ll keep gathering stories, the ones about Stan and the ones about Bill, and I’ll figure out the truth, if not about the name, then about the things that happened, and I’ll line them up for you: in the proper order, and with proper annotation, and with as little of the conjecture I’m making right now as possible. But the writing of this book is about more than just that, and that’s one of the things I’ve been grappling with over the last few weeks, writing and thinking such personal things.

I probably won’t ever know. Not that particular detail, so specific, and so likely inconsequential, no matter how much I want to read into it. I’ll keep gathering stories, the ones about Stan and the ones about Bill, and I’ll figure out the truth, if not about the name, then about the things that happened, and I’ll line them up for you: in the proper order, and with proper annotation, and with as little of the conjecture I’m making right now as possible. But the writing of this book is about more than just that, and that’s one of the things I’ve been grappling with over the last few weeks, writing and thinking such personal things.

I have no idea where I heard this story (yet another damning piece of evidence against my bibliographic skills, which before I started this project left very much to be desired), but it bears repeating anyway. Whether this is a yarn about a real place or an urban legend, a kind of artist’s parable, I don’t know, but it goes like this: there was once a little bookstore with only two sections. Over one cluster of shelves hung a sign that read Facts—nonfiction. And over the other? Truth. The fiction section.

When I first heard that little tale, fiction was the only thing I wrote—at least, the only thing I wrote of my own volition, and the only writing I shared with others that didn’t come back with a letter grade attached. I loved the story then, and I love it still, but it sounds different to me, after all these years, because my situation is different now. I write both. And I think about that anecdote now, and I wonder: why choose just one?

There are things in my novel that reference actual reality, but I didn’t put them there because I wanted anyone to learn anything. Fiction sits on the side of truth, at least when it’s doing its job as it should, and no one asks from it anything more than that—which is exactly as it ought to be. But nonfiction, that’s a different animal. There’s an implied derision in that simple word: facts. It conjures a sterility we remember from textbooks, and it’s a legitimate criticism: I am deeply buried in facts, trying to wade through the existing literature on the history of polio, and it can be stifling. I love to read the scientific papers of the time, which have a sort of sly elegance and cleverness the modern journals I studied in college totally lack, but the secondary sources, the academic tomes, are dry and impersonal in a way that feels to me almost heart-wrenching.

It’s important to provide accurate reportage, and a worthy accounting of the truth. But I love this story because it’s about people. People, and their lives and hearts and minds. People’s families, people’s memories, people’s heritage and hopes. Writers of nonfiction shy from those things, too often. Hoping, perhaps, that people will be able to extract the appropriate feelings from an endlessly unspooling reel of names, dates, and featureless interactions, or perhaps just afraid of accusations of bias or inaccuracy. But that’s the one thing the little bookstore parable has right: facts aren’t, intrinsically, connected to truth. The people I’m writing about deserve better than to be reduced to sweeping generalizations and gut-wrenchingly vague statistics. And they also deserve for someone to tell their stories correctly.

That’s why I look for those signatures, on Bill Stanley Willis William Bell’s letters, and why I pore so carefully over the accounts of those he worked with. Because I think that facts can tell us the truth, if we understand that there’s more there to speak than mere procedure. I love the way the whole world talks to itself: the way the specificity of these anecdotes becomes, always, universal, and the way semantic details can reveal intimate and tender emotions. It’s curiosity about people that leads me to recognize the gaps in my factual, biographical knowledge. It’s because I want explanations for the events and quotations and little quirks of behavior that allowed this thing, this crazy improbability that was the Kenny Institute, to happen the way that it did. And the discoveries I’ve made that way are what convinces me that even good math can add up to something greater than the sum of its parts.

That this story is so emotionally clear and so factually opaque is both its glory and its misery, and I’ve been sledgehammered by that a dozen times since I’ve gotten to Minneapolis. The folders and folders and folders of misfiled letters and papers shuffled like cards in a poker shoe over at the Historical Society are heart-stoppingly overwhelming, and the photographs and jokey newsletters written by Kenny’s patients feel like coming up for air. But I fight through the one to shore up the other. Because—like I’ve said before—I want people to see this thing the way that I do, and I know that means giving you something to latch onto that makes sense. Something that’s real. Something that’s true.

However you choose to interpret that, and whatever name it goes by.

18 Tuesday Jun 2013

Posted in Present Day, Real Life

Tags

introduction, me, minneapolis, moving, present day, real life

Firstly: I owe you an apology.

It’s been almost three weeks since I’ve posted anything, and I didn’t mean to take so much time off from updating the blog. This site is a vehicle for many things—cheif among them educating people about my topic, and keeping them up on the progress of the project—and I’ve been delinquent in both of those arenas. Because there are things I haven’t told you, because I haven’t had a chance. Because I was yanked from something I thought I understood into something that became much more than I bargained for.

It hasn’t been an arbitrary silence, however sudden it might have been. But it was a quiet that fell without warning, I know. (It feels especially egregious to me to have left you all hanging in the wake of my emphatic, anthemic last post.) What to me has been three weeks more chaotic than any in recent memory has been three weeks of radio silence for you. A blank space, a mystery. A vanishing act. And, at least right now, at the beginning of this post, only I know where I’ve reappeared.

The story I’m telling is all about perspective. And so, for the moment, is mine.

A little less than three weeks ago—three weeks that feels like forever, a miniature lifetime not quite my own—I packed up my apartment in Chicago, and watched the past I knew vanish into two dozen cardboard cartons. I’d been considering a move since February, but it wasn’t finalized until April, and nothing felt real until it was happening all at once. Until the internet access clicked off, and the counters had been wiped down for the third time, and the keys were just lying there, on the table where I used to toss the mail.

Three weeks ago, give or take, I threw my stuff into a U-Haul, and I came here. To this quiet house on a near-silent street, where on Sunday evenings no one breathes, and the sound of fingers on laptop keys bounces noisy off brand-new hardwood floors. A huge blackboard hangs on the wall, blank, for now, but raw with possibility, and on the floor a lamp beams out pale, softly colored light. It’s a grownup house, far more so than any I’ve lived in before, thoughtful in the way it’s put together, and the atmospheric statement it makes. I’m the one who made it that way, over three or four whirlwind days of trips to Target and IKEA furniture assembly, but there’s still something sort of bewildering about it. Something fragile and unreal.

Three weeks ago, give or take, I threw my stuff into a U-Haul, and I came here. To this quiet house on a near-silent street, where on Sunday evenings no one breathes, and the sound of fingers on laptop keys bounces noisy off brand-new hardwood floors. A huge blackboard hangs on the wall, blank, for now, but raw with possibility, and on the floor a lamp beams out pale, softly colored light. It’s a grownup house, far more so than any I’ve lived in before, thoughtful in the way it’s put together, and the atmospheric statement it makes. I’m the one who made it that way, over three or four whirlwind days of trips to Target and IKEA furniture assembly, but there’s still something sort of bewildering about it. Something fragile and unreal.

I live in Minneapolis now: a cozy two-bedroom on the outskirts of a neighborhood called Uptown, a few blocks away from Lake Calhoun. And the transition, which I thought would go so smooth and seamlessly, has changed me in ways I never could have imagined.

It feels strange to take any part of the story I’m telling for my own, and to feel connected to it so strongly in the present, but it’s been very much on my mind in these last weeks. What it means to be sidelined by something unexpected, and to vanish from a world you share with others into a different one, a smaller one, where you find yourself both more and less alone. A world that can be terrifying, in the possibilities that bloom when you least expect them, when a path you thought was modest and well-defined branches out to dozens of possible successes and failures.

It feels strange to take any part of the story I’m telling for my own, and to feel connected to it so strongly in the present, but it’s been very much on my mind in these last weeks. What it means to be sidelined by something unexpected, and to vanish from a world you share with others into a different one, a smaller one, where you find yourself both more and less alone. A world that can be terrifying, in the possibilities that bloom when you least expect them, when a path you thought was modest and well-defined branches out to dozens of possible successes and failures.

Only so much of any intensely personal journey can be shared. There are limitations on words, ones I grapple with every day, in trying to illustrate the stories of people whose heads I will never entirely inhabit. (Nor is this challenge confined just to the problems of history; though I haven’t talked about it here, I’m also a fiction writer, working on a novel in tandem with this book.) I haven’t even defined them all for myself, the things that have changed since I came here, and that makes the seismic shifts even more difficult to articulate.

But I can say this, and easily enough: even with an overstuffed U-Haul, and all the things I brought with me, I left even more behind.

I came here to be closer to my research. To take the next step in teasing out the truth of the saga I’ve promised to recount, and get a better idea of how to go about the writing process itself. My apartment is a twenty-minute drive from the Historical Society in St. Paul, where they keep those archival boxes I’m always talking about, the ones that spill out stories like a thousand points of light. The site of the original Kenny Institute, the building stripped of its façade (and its purpose), but still recognizably connected to the one in the photo at the top of this page, is a ten-minute drive from my apartment. If there are more people to interview, they are most likely here, or at least their descendants are; my new friend Russell lives in a nearby suburb. The modern Sister Kenny Rehabilitation Institute is (or was, but more on that later) still operating in the Twin Cities, and how much they might be able to tell me of what I want to know remains to be seen.

I knew I was coming here for a reason. But I didn’t realize it wasn’t any of the ones I’ve listed. I didn’t realize that what I’d find in this new home was something I never knew I was looking for, in the midst of a landscape almost entirely divorced from the map I followed to get here.

The first time I ever came to Minneapolis—this city itself, not its wayward brother St. Paul, where I spent research weekends two blustery Januaries in a row—was the middle of this last April. It was the trip on which I found the place I live, when after a long day of frustration and disappointment I stepped into my new living room and asked, “Where do I sign?” But the trip wasn’t supposed to focus on the hunt for an apartment, which, even with my lease in Chicago rapidly running down, felt more like a lark than anything else. I was here for something on the surface very different, but equally dear to my heart: a yoga teaching seminar with the brilliant Matthew Sanford, whose work I’ve admired ever since I found out about it last year.

I got my yoga teacher training certification about a year ago, at the fitness-focused studio where I practiced in Chicago; it seemed like a good opportunity, and a good next step for something that had become incredibly important in my life. I have always lived amidst deafening noise, struggling with anxiety and a chronic lack of confidence, and learning to breathe through yoga infused both my personal and creative lives with new energy, new hope. It was an arena where I thought I might find a deeper connection between myself, and the things inside my head, and other people, and the outside world, all spaces segregated inside me by improbably high walls. But before long I realized I didn’t have the time in my life, or any real longing in my heart, to teach conventional yoga. Leading the Spandex-clad denizens of Wrigleyville through asanas—the fancy word for poses—meant mostly to tone a part of their body with a similar name, was not the personal development I needed.

Matthew Sanford sometimes teaches yoga to people who wear Spandex, and care how they look from the rear. (I know because I’m one of them.) But he also teaches “nontraditional” yoga to people with disabilities—trying to bring to their lives not just the traditional benefits of yoga (mindfulness, calm, self-reflection, and, yes, fitness) but also something else, something bigger. A sense of their bodies as intrinsically whole, and intrinsically valuable, still beautifully connected to and conversant with their minds, whatever their practical limitations or neurological sensations might be. And he does it all from the wheelchair he’s lived in since he was thirteen, his world transformed instantaneously by a car accident.

The world inside my head softens, when someone speaks directly to my heart. Just reading about Matt’s work melted me, and I knew right away that that was what I wanted to be involved with. The practical challenge of figuring out how to adapt the essence of poses without losing what they try to tell us about the way we exist in the world (“teach the experience,” as Matt puts it), and the subtler challenge of really being with someone as you go through that together. The challenge of real presence.

The world inside my head softens, when someone speaks directly to my heart. Just reading about Matt’s work melted me, and I knew right away that that was what I wanted to be involved with. The practical challenge of figuring out how to adapt the essence of poses without losing what they try to tell us about the way we exist in the world (“teach the experience,” as Matt puts it), and the subtler challenge of really being with someone as you go through that together. The challenge of real presence.

I took his first training session, like I said, in April, and then the follow-up, second-level program in May. What happened inside those light-filled rooms was amazing to me, and unlike so much else in life it existed with all the superfluity stripped away. This is real, Matt kept telling us—the teacher trainees, and his students, too. This is real life.

And I thought, yeah.

Because it’s the same way I feel about this project, and my novel, too, and the parts of my personal life that I hold the most dear. It speaks to the same impulse as the concept of art, and the sanctity of language—which, for me, is just the most convenient stand-in for the idea of honest communication in general. To put one’s hands on a yoga student, or to sit with someone as they confide a transformative story, or write the story of something that never happened, but could have, and share it with someone who understands—that is the closing of a chasm, the bridging of a gap. It is a stretch toward truth by two parties who are both interested in finding it, rather than avoiding it, for fear it might feel uncomfortable.

Matt teaches his adaptive classes at a place called the Courage Center, a facility with both in- and outpatient clients, working to help those with disabilities live more independent lives. And in a partnership that seems to have rocked the local healthcare world significantly, but that I had managed not to hear about until I got here, it was recently absorbed into one of the local hospital systems—the same one that manages the modern Sister Kenny Institute. Neither one will exist any longer independent of the other. And what that meant didn’t hit me until I filed the paperwork to assist in Matt’s class, and got an e-mail back from the volunteer liason at the newly established conglomeration: “Volunteering at Courage Kenny Rehabilitation Institute.”

I came here in part to be near the Institute, which I hear is still doing pretty remarkable work. But I never imagined I’d work there, or in the place that it’s becoming: a place sort of sentimentally near to my heart, which is both new and old and at a crossroads. Kind of like me.

One of the things I love about the Kenny story, and that of the Kenny Institute specifically, is the sense of cohesion it provided for the people who lived there. The hospital’s philosophy gave the patients a framework for understanding the world and their place in it, and whether and how what had happened meant that had to change. It gave them a way to weld everything together, to take a blast furnace of confusion and frustration and anger and put it to work. And that insistence on wholeness of body and soul, on not just picking up the pieces but taking the time to fit them together into a life that made sense, was everything.

I write about wholeness a lot, and spend a lot of time reflecting on it, but it’s something I’ve never really had. The welded life I love so much is one I’ve never lived. The things that I loved, and the different aspects of the person I wanted to be, and the concerns that I always thought were important, never had a chance to manifest all at once. I could do a handful of things at the same time, and if something crucial was missing, I would go looking for it when something else changed, or I found more time, or things weren’t quite as difficult. When I was less anxious about how people might see me, or what they might think, if my carefully curated worlds collided.

But it isn’t true. The realization came suddenly, and hard, in this new living room: that the day when things are easier, or I have more time, or fewer preoccupations, is never going to come. There are a million moments of right now in a lifetime, each one different, and weighted down with context. But right now is the only thing that there will ever be.

I was eighteen years old when I moved to Chicago. I knew a lot about what, and who, and where, I didn’t want to be. (An Apple computer salesperson, stuck in the suburbs of Baltimore, four years out of college and without any idea where to go, or whether I might ever fit in.) But I never felt truly empowered to choose something different. I never found a community where I could be myself, or people with whom I felt compelled to get seriously involved. I yearned for independence: the feeling of independence, of agency, which is far more ephemeral than people realize. I lived on my own for years without ever feeling empowered to drive my own life in the direction I felt it was really meant to go.

I spent a long time shy and embarrassed about my writing, about my past, my philosophy, my life. I still haven’t talked very much about my background, but I’m planning to; I want you to know me, and why I’m doing this, as well as you come to know the people who populate the sepia picture I’m painting. I don’t want to write myself into my own book; the end product this blog teases is about Elizabeth Kenny, and the people she helped (and some of those she couldn’t), not about me. But talking about the process is inevitably a way of talking about myself, especially now that my thousand shattered lives are sharpening, finally, to a single point.

I lived a yoga life, before. A life as a fiction writer, and a separate life as someone embarking on a research project that seemed impossibly audacious, given my background: an undergrad degree in biology didn’t seem legitimate enough to speak on such a momentous topic, and my five years in the pediatric ER of Johns Hopkins Hospital felt like an inadequate explanation of my interest in medicine. I never talked about my writing with strangers. I’ve lived lives in secret, and lives that were highly visible but not quite true. I’ve never spent much time trying to fit into others’ expectations, but I have spent long years being wistfully misinterpreted by the people around me. I have tried silence, and I have tried angry, self-righteous defiance, but I have never tried acceptance. I have never stood still in the midst of myself and acknowledged the things about me that are unchangeably true, or honestly tried to escape the traps I fell into by accident, and than stayed in out of fear and inertia, the ones filled up with easy, painful lies.

What does it mean to embrace being lost, when it takes even more bravery to admit to being found? There is no agreed-upon scorecard in life, at least not one any useful number of people will agree on; you will never know if you’ve “won.” The only judge worth listening to is the barely audible voice inside your head, whispering breathily that you’ve done the right thing, and it’s all too easy not to listen. Because what if you’re wrong? What if it’s made-up, and this thing seems so wonderfully laden with potential just because it happens to be better than the terrible situation you’d been mired in before? What if you are merely the victim of a fresh landscape, and the wishful thinking that comes along with it?

What if it doesn’t matter? Who the hell cares? Wishful thinking is a cynic’s synonym for hope. Perception is reality. And we write our own stories every minute we’re alive.

Everything is different here. The weather is different: unseasonably cool and sticky, and unremittingly gray (unusually, the locals promise), with a ceiling of clouds that peel like wallpaper. The people are different: they move more slowly than I’m used to, and talk more sharply, about places and things whose names I don’t know. The neighborhood is another world, with its quiet residential streets and quilted flower gardens, sitting apart from the vintage shops and bike vendors and dive bars on Lyndale. There are as many restaurants in my entire neighborhood as there were in the five blocks around my old place. Even more of the twentysomething hipsters stalking down the streets sport slashes of neon color in their short-cut hair, but they look more out of place than they did in Chicago. More ostentatious, but quietly so, circumscribed in their defiance.

I am different here, but not because of any of that. Because when everything you know falls away, your first instinct is to do everything in your power to find those things again, and snatch them back, keep them safe. And the liberation in realizing that maybe they aren’t the ones you need after all—that is beautiful, and terrifying. And something it’s going to take a lot longer than three weeks to sort out.

My journey is far less dramatic than that of the kids that I write about. I have not been blindsided, traumatized, or terrorized (at least not in the short term); if my world has been upended, it has been by something that at least on the surface I chose. But that doesn’t mean I know exactly where I am, or have a good grasp on where I’m going, or that keeping the faith is always—or ever—simple. It’s a positive change, this one that I find myself so unexpectedly facing, but it is one I feel unprepared to handle, even as I hope to use it as a springboard to the kind of wonder I’ve never successfully held. I’m hoping I can learn from them—Kenny’s kids, the ones that I feel I’m watching over, now, in this place with so many memories, and so many echoes of beauty. With fortitude, and a little bit of luck, I’m here not just to tell their story, but to follow their example.

I am definitely still a little lost here. But sometimes, when you’re lucky, in being lost to the world, you get a chance to find yourself.

28 Tuesday May 2013

Posted in Introduction, Kenny Institute, Society

There is a lot of amazing stuff, in the stack of ludicrously heavy filing boxes that make up the Minnesota Historical Society’s “Kenny Papers.” But one of the more arresting parts of the collection is a thick folder of letters, newer than most of the things housed there, and without their musty smell and air of fragility.

Some of the letters are written by hand, in the beautiful looping calligraphy kids don’t learn anymore; I certainly couldn’t replicate those effortless, soaring curves. Others are tapped on typewriters, or printed in erratic monospace font, spat out unceremoniously by early word processors. They come on paper of every imaginable color and size, some intricately folded, others not at all. There are short ones, barely a paragraph, and ones that seem to go on forever, and it’s obvious that none of them say anywhere near as much as they could. Some are creased razor-sharp, the lines so straight they seem to have been written across a ruler; others sprawl and squirm, thick paper rippled by moisture, the residue of sweaty hands or falling tears.

I’d swear that even after all this time–exactly as many years as I’ve been alive–some of them still carry a faint whiff of elegant perfume.

They’re letters written about the still-extant Sister Kenny Rehabilitation Institute on its 50th anniversary in 1992, when a prominent Minneapolis newspaper asked former patients to contribute their memories of the time they spent there. And the differences are semantic, because the content of every single one is the same. I’ve never seen the initial request, but it must have been restricted to the very earliest patients, from the forties and very early fifties, the ones who knew Sister Elizabeth Kenny personally. Or maybe they were simply the ones who felt moved to write in en masse.

The letters are incredibly, unreservedly warm, and to a one palpably grateful. These people, fifty years later, remembered their time at the Insitute—or “Kenny,” some of them called it, “my time at Kenny”—with nostalgia almost unto joy. The time they had spent as inpatients in that squat little building in the heart of Minneapolis was time they’d come to treasure. And they wanted, so exuberantly, so delightfully, to tell their stories. To explain how their brimming, happy lives had played out, and thank everyone involved, even though so much time had gone by that most of the Institute’s original staff had passed away.

It’s fantastic. There really isn’t any other word for it. I came to these things after months immersed in the kind of desperate material I spoke at length about in the last few posts, a world drenched in fear and viewed perpetually in the negative: with the deep pessimism of resignation, and in garish, otherworldly colors. I saw none of that here. And what I saw instead enchanted me.

Who in the world was this woman, I wanted to know, and what was so different about this place?

As it turns out…that depends very much on who you ask.

Even though I’ve been researching her story for upwards of a year now, I’m still trying to tease out fact from fiction, and half-truths from the ones so complete they’ve been embellished into legend. It’s one of those stories, the best kind: where the most hyperbolically ridiculous statements are the ones most likely to prove true, and the ordinary things, the ones that establish a simple, everyday rhythm of life, are the toughest to pin down.

The lives of extraordinary people aren’t so different from anyone else’s, day in and day out. But those aren’t the things people remember.

Born in 1880, Elizabeth Kenny grew up in rural Australia, part of a large, rambunctious family with a formidable number of children. Easily the most fearless and outgoing member of an already free-spirited group, when she broke her arm as a teenager, she convinced the doctor who set the bone to take her on as an apprentice. (Though she would later claim various nursing certifications, this may be the only supervised medical training she ever got.) After a couple of years spent working on and off for Dr. McDonnell, she ventured out on her own to serve as a “bush nurse.” It was somewhere in the depths of these years, making house calls on horseback to families who lived dozens of miles from anything approaching “civilization,” that she started treating polio cases.

Born in 1880, Elizabeth Kenny grew up in rural Australia, part of a large, rambunctious family with a formidable number of children. Easily the most fearless and outgoing member of an already free-spirited group, when she broke her arm as a teenager, she convinced the doctor who set the bone to take her on as an apprentice. (Though she would later claim various nursing certifications, this may be the only supervised medical training she ever got.) After a couple of years spent working on and off for Dr. McDonnell, she ventured out on her own to serve as a “bush nurse.” It was somewhere in the depths of these years, making house calls on horseback to families who lived dozens of miles from anything approaching “civilization,” that she started treating polio cases.

The story of her very first encounter with the disease is a great one, and I won’t tell it here, at least not right now. But the crux of the story is contained in a single telegram sent by Kenny’s mentor, after the young, terrified nurse reached out for help.

“Infantile paralysis,” Dr. McDonnell told her. “No known cure. Do the best you can with the symptoms presenting themselves.”

And so Kenny did—and her young charge made a full recovery, along with the half-dozen others who fell ill in the outbreak. She had no idea what you were “supposed” to do with polio patients, or even what was assumed to be wrong with them. It’s a big leap, actually, from “this patient can’t move so well” to “this patient is paralyzed,” and in circumventing the conventional wisdom—not because she was rebelling against it, but because she didn’t know what it was—Kenny found loopholes and inconsistencies in that thinking that led her to an entirely different method of treatment. Among other things, gentle exercise took the place of immobilization, and intense heat therapy stood in for bizarre drug injections—and the results were spectacular. (I am being, here, intentionally vague; a further explanation of these competing treatments, and the way Kenny’s approaches to neurology and psychology intertwined, is in the pipeline.)

With a couple of brief detours into other endeavors, Kenny worked from that point forward rehabilitating people with disabilities who had been written off as hopeless—not just polio patients, but also kids with cerebral palsy and other neuromuscular disorders. As word of her method (and its effectiveness) spread, so did the controversy: she claimed to observe dramatically different symptoms than had been recorded by anyone else, the symptoms on which her method was based, and an air of self-righteous indignation started to gather around her.

One of my very favorite lines in her (spectacularly funny, and spectacularly fictionalized) first autobiography, published in 1943, tells you pretty much everything you need to know about her manner of interacting with others: “Some minds,” she says, “remain open long enough for the truth not only to enter but to pass on through by way of a ready exit without pausing anywhere along the route.”

This was not a clever aphorism devised to get a smile out of readers. It was a philosophy by which she lived, and if she thought you suffered that particular affliction, she was not shy about telling you so. A contemporary journalist might have called her the “Angel of the Outback,” but Elizabeth Kenny was hardly a saint. (Nor was she a nun, despite being widely known as “Sister” Kenny; that was a title bestowed upon decorated nurses in the Australian army, where she served during the First World War.)

Part of the reason I decided to do this project is the frequency with which people still try to discredit Kenny, on the rare occasions when the story is dragged out of the historical attic, and that modern prejudice is rooted in the ferocity of the original controversy. Doctors loathed her, almost to a one, because everything about her rankled—her gender, her lack of credentials, the fact that she said they were wrong—and when they rebuffed her, she pushed back with equal ferocity. She was right, obviously, and everybody else was not only wrong but also incredibly stupid. (This is a diplomatic strategy that tends not to further negotiations.)

Part of the reason I decided to do this project is the frequency with which people still try to discredit Kenny, on the rare occasions when the story is dragged out of the historical attic, and that modern prejudice is rooted in the ferocity of the original controversy. Doctors loathed her, almost to a one, because everything about her rankled—her gender, her lack of credentials, the fact that she said they were wrong—and when they rebuffed her, she pushed back with equal ferocity. She was right, obviously, and everybody else was not only wrong but also incredibly stupid. (This is a diplomatic strategy that tends not to further negotiations.)

It wasn’t until 1940 that she landed in the United States, and there’s some confusion about why she ended up here in the first place. To hear her tell it, she was sent by the Australian government and its public health counsel to spread her technique as a point of pride for her country; less generous accounts sometimes imply that they wanted very badly to get rid of her. But after unsuccessful presentations at hospitals in New York and Chicago, just as she was about to return to Australia, she met a duo of sympathetic doctors from the University of Minnesota hospital…and it was in Minneapolis that the other side of the story blossomed.

Kenny might have been combative with doctors (and, when necessary, politicians, the press, and her own staff). But to her patients, she really was something like a saint. Gentle and attentive, she was their constant defender from a system that didn’t take them any more seriously than it took her. They became co-conspirators, in a way, and it was an arrangement that seemed to strengthen everyone involved. Kenny didn’t have time for anybody’s—well, it’s not exactly a family-friendly word. But she always had time for her kids.

Russell Papenhausen, the gentleman I interviewed a few weeks back, who I’ve mentioned a couple of times, lights up when he talks about her. At age fourteen, he was one of her first patients in Minneapolis, treated before the Kenny Institute (her very own 80-bed hospital, founded in 1942) even existed. And he put it more simply, and with more authority, than any of my pretty words ever could.

“She was a marvelous woman,” he told me, breaking into a mischievous smile. “She put the fear of Christ in the grownups and nothing but love in the youngsters.”

This was the one time that the patients’ voices won out, and, almost overnight, the beleaguered nation fell in love. Everyone in a position of prominence during the height of the polio epidemics gathered around them many dozens of sycophants; Basil O’Connor, the (extremely reluctant) director of the March of Dimes, was lionized by many, chief among them President Roosevelt. But not many people had letters sent to them asking, in all seriousness, “Would you let me know when it would be practical for you to receive a 15 lb. ham?”

This was the one time that the patients’ voices won out, and, almost overnight, the beleaguered nation fell in love. Everyone in a position of prominence during the height of the polio epidemics gathered around them many dozens of sycophants; Basil O’Connor, the (extremely reluctant) director of the March of Dimes, was lionized by many, chief among them President Roosevelt. But not many people had letters sent to them asking, in all seriousness, “Would you let me know when it would be practical for you to receive a 15 lb. ham?”

A reporter named Inez Robb wrote the following, after her first visit to the Institute, with the breathless lack of objectivity endemic to midcentury journalism:

When I went out to the institute, I went up to visit a patient in the big ward which houses 29 boys ranging in age from 6 to 16. When I came into the ward, I saw a sight that stopped me in my tracks. Two lively kids of seven were wrestling vigorously in a hospital bed. It was a rough and tumble scrap.

At that moment, the nurse reappeared.

“Tommy! Johnny!” she said authoritatively. “Stop that at once! Tommy, you know you are not allowed out of bed. Get back into your own this instant!”

The kids looked sheepish. Tommy, a beguiling imp with big black eyes, got back into his own bed.

“Kids have so much pep,” the nurse said. Kids with infantile paralysis with pep! With too much pep!

“It seems like a miracle,” I said helplessly.

Kenny hated the word miracle—because it embarrassed her, she always claimed, and because it wasn’t true; I suspect it had more to do with the fact that it gave God credit she would have preferred to keep for herself. But of course it seemed like a miracle. It seemed like a miracle to the uncountable, unfathomable number of parents who had been told their child would never walk again, and to the children who’d believed their lives were forfeit—but for very different reasons. In her baker’s dozen years in America, Kenny tiptoed, and sometimes blithely trampled, the vanishingly thin line between what society expected from a great healer of polio victims and the kind of compassionate care those people actually needed.

Kenny was beloved by the nation for the results she produced: the Kenny Institute’s recovery rate was vastly greater that of any other treatment facility’s—about three times higher than average. More of her kids walked; eventually some ran and jumped and fought for our country in the Second World War (including my new friend Russell). Few wore braces or endured the spinal curvature common among polio survivors; if they used crutches, they were the short forearm type known then as “Kenny sticks,” rather than the awkward underarm variety, the kind you were supposed to use when you broke an ankle, and which gained an extra sense of pathos in their permanence. The science, however controversial, was sound; the therapy worked. Kenny’s kids got better.

But her patients didn’t love her because she made them well. They loved her because—against all odds, in a situation just once removed from the fires of hell—she made them happy.

I think my favorite thing in the Kenny papers—more touching than the huge box of thank-you letters, more chaotically revealing than the hundreds of disorganized photographs—is a box of newsletters, crudely typewritten sheets the patients at the Institute put out at various intervals in the 40s and early 50s. They were sent out to kids’ families and circulated inside the clinic, blurry duplicates on brightly colored sheets of cardstock, rife with good-natured ribbing and inside jokes. The young writers gossip innocently about their therapists and doctors and nurses, gush about the photography classes they’re taking or the movies brought in for them to watch, speculate about what they’ll do when they get out, who they’ll be when they grow up. They tease with enthusiasm old friends who come back for outpatient visits, especially when their subpar performance in the checkup meant they’d have to come back for a kind of remedial stay.

I think my favorite thing in the Kenny papers—more touching than the huge box of thank-you letters, more chaotically revealing than the hundreds of disorganized photographs—is a box of newsletters, crudely typewritten sheets the patients at the Institute put out at various intervals in the 40s and early 50s. They were sent out to kids’ families and circulated inside the clinic, blurry duplicates on brightly colored sheets of cardstock, rife with good-natured ribbing and inside jokes. The young writers gossip innocently about their therapists and doctors and nurses, gush about the photography classes they’re taking or the movies brought in for them to watch, speculate about what they’ll do when they get out, who they’ll be when they grow up. They tease with enthusiasm old friends who come back for outpatient visits, especially when their subpar performance in the checkup meant they’d have to come back for a kind of remedial stay.

Because, the authors declared, only half joking, they knew nobody ever really wanted to leave.

I find myself holding my breath while I read them, like suspending the present can take me back in time, or like if I wait long enough or attend closely enough I might be able to inhale the stale air, with its sweetly rancid scent of rambunctious kids at play. There’s plenty of irony in the Kenny Stretch, and more than a little dark humor, but hardly anywhere do you see a forced smile. Isn’t this such a weird, messed-up world we live in? they ask, unselfconscious, and wise beyond their years. Isn’t this awful? Aren’t we bizarre?

Yes. And gloriously so. Because their lives belonged to them, and them alone, and it’s clearer here than anywhere else. Nobody else got to decide how they felt, or what they were afraid of. They might have been far from home, stranded apart from everything they knew or understood, but this new world was one they were building themselves.

The Kenny Institute was no less of a microcosm than any other inpatient facility—more so, actually, with its tight restrictions on visitors, and conspiratorial sense of community—but it wasn’t a place where you waited for your life to start up again. It was a place where you celebrated the life you still had, the one you were living, because someday was far away, and you were still exuberantly breathing right now. Though she never stated it explicitly herself, it’s obvious that it wasn’t just Kenny’s therapeutic concept that differed from the norm. Her philosophy was wildly different, too, and its core postulate was this: that recovery wouldn’t happen unless you were deeply invested in it yourself, and that in order to be willing to sink such physical and emotional effort into an outcome that was ultimately so uncertain, you needed to value yourself right now.

Her patients had to understand what they were working for, and that that work was something they did for themselves. Not for some anonymous coalition of doctors who poked and prodded at your limbs and scribbled down incomprehensible numbers on a chart, who wouldn’t tell you if you failed. Not for parents who worried that a lingering disability meant giving up on everything they’d hoped for you in life—not to mention what the neighbors would say, or how the checkbook would balance. Not to keep up with siblings or friends or an amorphous notion of what it meant to have dignity.

And—perhaps most importantly—not even because Sister Kenny told you to. Sister Kenny was not afraid of telling you to, and in no uncertain terms, but—unlike pretty much everyone else in the rehab community, at least according to the patients whose accounts I’ve read—she wouldn’t make you do much of anything at all. If you couldn’t prioritize your own recovery, couldn’t take the initiative to focus on getting better—which meant deciding that getting better mattered, which in an uncertain world must have meant you mattered, at least enough to try—she knew she couldn’t force you to succeed, any more than those stubborn doctors could force her to shut up.

You couldn’t just choose to get better.

But you could choose to live.

Put even more simply: “back to normal” wasn’t under your control, or, however skilled her hands and gilded her reputation, Sister Kenny’s. Recovery depended on factors no doctor or therapist could possibly foresee, on the degree of stripping in the wires, on the strength and stubbornness of your body. But better—partly in the sense of performing “better,” to whatever degree you accomplished that, but also partly in the sense of feeling better, feeling safer, more whole—that was a choice. And it was one you had to make; no one one else could make it for you.

That kind of responsibility was terrifying, especially to kids coming out of hospitals where they’d been treated as all but inanimate. But it taught them to stand up straight—in more ways than one—without feeling like they were being puppeteered. Not everybody remembers the Kenny Institute as a wonderful place to be, and it wasn’t an unconditional blessing for anyone. The reality of this situation was impossible to ignore—even if it was, eventually, possible to escape—and patients were asked to face it head-on far more often under Sister Kenny’s care than at most other facilities. The physical and psychological demands she placed on children widely believed to be both incredibly fragile and uselessly damaged were enormous. But those expectations were also an endorsement of personhood, and a gesture of respect, and for even the youngest of her patients, those confidences were transformative.

“You were lucky,” Russell’s wife told him, at the end of our second interview, after we’d fallen silent, exhausted, companionably sharing a plate of homemade cookies she’d brought.

He looked up, quizzical, in the middle of a bite.

“Not lucky to have polio,” Andree amended, waving a hand. “But lucky she came along when you did.”

It was exactly the same sentiment expressed by the wire-service reporter I quoted earlier, in a different, later piece: the children of Minneapolis, at that particular juncture of history, were the “luckiest in the world.”

Not because they were safe; nobody in the world was that, in the midforties, from polio or anything else. Not because there was nothing horrifying about their world, or because that world was free from danger. Because they had the thing that we all so desperately need, and that so much of the rest of the country at that point lacked.

They had hope. And more than hope, they had agency: the courage to find their own voice, and the fortitude to know that the only way to keep their illness from defining them was to write that definition themselves, before anyone else had a chance.

This is the story I’m telling. And this is “A Louder Silence”: the embrace of volume, and clamorous voice, in the midst of a world determined to strip away all the noise. The chattering static of undisguised reality, and the way it starts to sound like music, if you tilt your head just exactly the right way. And the other kind of silence, lurking underneath such fearless self-expression: the ability to sit quietly inside yourself, to find some kind of peace, without needing to thrash away at endless, anxious insecurities. To shout with joy, rather than defiance.

This is the story I’m telling. And this is “A Louder Silence”: the embrace of volume, and clamorous voice, in the midst of a world determined to strip away all the noise. The chattering static of undisguised reality, and the way it starts to sound like music, if you tilt your head just exactly the right way. And the other kind of silence, lurking underneath such fearless self-expression: the ability to sit quietly inside yourself, to find some kind of peace, without needing to thrash away at endless, anxious insecurities. To shout with joy, rather than defiance.

Of course, it’s not always that easy. It’s probably never as easy as I just made it sound. But it was possible. It was beautiful. And this silence deserves to be amplified.

Welcome home.

25 Saturday May 2013

Posted in Introduction, Society

She is grim and anxious, captured in this set of black-and-white photographs. Her small body rigid, she stands barely balanced on a pair of short forearm crutches, mouth set and sharp as a razor blade. You can see how much she needs this step, and how hard her heart must be beating, keeping time with the shaking of her weak, tangled muscles as she moves. Her therapist’s hands are light on her slender legs, her ankles and calves, moving them forward one at a time, showing her where to go, making the effort she is still too wrung out to manage by herself. Her short hair is neatly braided, pretty and incongruously ordinary against the back of her neck. She’s maybe eight years old, or a little older than that, and she looks exhausted already, holding the weight of the world in her small hands, eyes fixed straight ahead.

And then something changes. I don’t know what happened in that moment, in the flicker of time between those shutter flashes (if shutters, or flashes, were even things cameras had back then). I wish I could have been there, to see exactly what elapsed between the fourth and fifth snapshots. But whatever it was—some whispered word of encouragement, or some feeling of triumphant familiarity—looking at that last picture is like watching the sun come up. Standing there, laughing, she is radiant on those crutches, this skinny grade-school girl. Elfriede Kohler is the happiest person in the world.

The day I saw that picture was the day I started to understand. What I was really looking at, and what someday I would be writing about, and what it would come to mean, and the ways that it would change me. Those photographs are the culmination of a lengthy scrapbook, lovingly assembled by someone at the clinic where Elfriede was treated, chronicling her progress from the depths of illness to partial recovery and discharge. The brown kraft paper is rippled and torn, and pictures have fallen out here and there, leaving tantalizing holes in the story that the handwritten captions don’t quite manage to fill.

And I sat there in the library, feeling the weight of this book in my lap, as fragile and enduring as the girl it preserves, and I knew I never wanted to give it back. Not just because the feelings were so profound. Because—at least in part—I was starting to grasp just how incredibly rare they were.

Moments like Elfriede’s don’t come along very often, in these stories, but even when they do, they sit far down the line from the place we left off. The illness was a dark, purgatorial space, after the before but just before the after, and no matter who you were, and what you might eventually achieve, the earliest forays into this new, unstable life were as terrible as anything that preceded them.

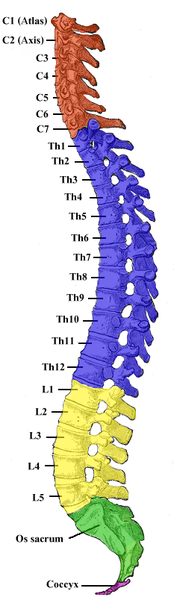

Polio’s paralysis is strange and unpredictable: its boundaries are fuzzy, its consequences vague, and, at least at the beginning, its permanence unclear. Weakness powerful enough to put someone in an iron lung could abate entirely within weeks, but someone else’s comparatively inconsequential limp might never get better at all. The effects are hardly ever symmetrical, nor are they especially well-contained: one side of the body is almost always much more heavily involved than the other, and even devastated limbs usually have some muscles that still work.

Even more uncannily, for all the glittering pins and needles of the illness itself, once the infection clears, sensation is rarely ever affected. So much of the world stays intact: the feel of the damp sheets against your body, the nurses’ rough handling of your tight, aching shoulders, the bright-lit pain that still pulses through your body, random and blinding as lens flare. It’s only your ability to interact with it that changes.

It doesn’t make sense, the straining that happens inside you, and the cruel disconnect between what you feel or imagine to be possible, and what you find really is. Some people talk about a sense of disembodiment, like that part they can still sense but can no longer command or comprehend doesn’t even belong to them anymore. More often, though, in recounting their experiences, people don’t talk about it at all. They are lying desperately ill in the contagion ward, and then they are in therapy, transferred somewhere else to reboot, to get better. The transition is so fast and so disorienting, and the things on either side of it so bold, that it doesn’t even stand out.

Every so often, someone will bring it up, often a little dreamily, like they’re only just realizing it’s true: I guess that was the last time I walked on my own.

Knowing seems to bring them comfort.

It was clear right away that something was terribly, terribly wrong, but it often took a long time to figure out just what it was. The moment it was possible to endure being touched again, the doctors swarmed back in—more often than not to contain you, compress together all your pain and confusion and complicated feelings and literally bind them to your body. Not just weeks but months of recovery were spent lying strapped down in bed, in an attempt to prevent further damage to weakened muscles. Infants were put into body casts; older children and adults found themselves racked on “Bradford frames,” traction-like devices that held them stretched out, often with their arms at right angles.

“The immobilization is maintained for a period of eight weeks, a t which time a second muscle test is made…. If exceptional improvement is shown, this immobilization…is repeated,” a prominent 1941 textbook, Dr. Philip Lewin’s Infantile Paralysis, instructed. These eight-week periods were to be repeated indefinitely, but were “seldom continued for more than six to eight months.”

t which time a second muscle test is made…. If exceptional improvement is shown, this immobilization…is repeated,” a prominent 1941 textbook, Dr. Philip Lewin’s Infantile Paralysis, instructed. These eight-week periods were to be repeated indefinitely, but were “seldom continued for more than six to eight months.”

As if that’s no time at all. As if everyone old enough to understand what was happening to them didn’t use that time to think about what would become of them after all this was over. Didn’t lie in bed worried and helpless, and knowing all too well what would happen if it didn’t work. If they didn’t get better.

People don’t talk about the transition, and those early days and weeks of recovery. But they talk about the extremes to which they later went to fight for normalcy. They talk about being haunted by a stigma they were desperately trying to avoid.

There’s a poster that’s frequently reprinted in historical retrospectives of the “polio years;” I first saw it in a 2005 exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum of American History in Washington D.C. Created for a vaccination awareness campaign in 1956—the second summer the shot was available—it shows two different pictures, dramatically-split screened by contrasting backgrounds. On the right stands a smiling grade-school girl in tight buns that bear a passing resemblance to Princess Leia’s, balanced awkwardly on wooden crutches, the angle of her slender arms calibrated to imply even more deformity than she seems to suffer. On the left, two able-bodied children stride confidently through a field, wholesome hands intertwined.

This, the caption reads, above the happy siblings. Not this, above the bravely grinning girl. Vaccinate your family now

This. Not this. This. Not this.

This was the world the many thousands of people paralyzed annually by the disease in the U.S. alone had to live in.

Every single depiction of polio, every warning against it, characterizes the disease as a hideous specter, sometimes literally so: in a film called The Crippler, produced by the March of Dimes, the illness moonlights as a grossly elongated shadow, looming darkly over unsuspecting homes. Polio was horrifying, of course, and more than likely this visceral repulsion accomplished its objective: eliciting donations, raising awareness, and getting kids vaccinated, when that time came. But in associating the illness with the grotesque, its victims were tainted that way, too. As disgusting and contaminated, or else tragic and courageous, almost martyred, helpless young sacrifices to a noble cause. We put these kids up on pedestals even as we shrank from them in terror.

Having polio no more made you brave than it made you broken. It meant you were in the wrong place at the wrong time, that you shared the wrong ice cream cone or dove in the wrong swimming pool. The poster child was a cultural fantasy, not a reflection of reality.

But how do you understand that, at four years old, or fourteen? You’d seen those pictures, unless you’d been living under a rock since the day you were born. You knew what it meant, to have had this happen to you. And you knew that the only way to be okay again, to avoid being pitied or lionized, was to get better. All the way better. Even the kids in those posters knew it: “Help me walk again,” a picture of a child in a walker pled, and a happily skipping boy was triumphantly captioned, “Your dimes did this!”

Getting better became the only thing that mattered. The only way to feel real again. And not just getting better. Getting well.

In the mem oir Warm Springs, about her surgical rehabilitation at FDR’s famous polio hospital, Susan Richards Shreve recalls her younger brother asking if going in for reconstructive operations frightened her.

oir Warm Springs, about her surgical rehabilitation at FDR’s famous polio hospital, Susan Richards Shreve recalls her younger brother asking if going in for reconstructive operations frightened her.

“I’m not scared,” she told him. “The next time you see me, I’m going to be a different girl.”

“What kind of girl?” he asked her.

“A perfect one.”

It wasn’t just the specter of posters in shop windows and hyperbolic movie reels that made this seem so crucial. It was the reality you lived, day in and day out, in most inpatient rehab facilities. After the restraints finally came off, patients were often started on aggressive exercise regimes, hoping to strengthen them enough to get them back on their feet. The goal, always, was sitting, standing, walking, no matter how much supportive bracing that required, or how much it might hurt.

The acceleration was dizzyingly brutal: kept from doing anything for so long, now you were expected to do everything, and the goal wasn’t really to make you feel better. It was to achieve something as close to normalcy as possible, no matter how strenuously your weakened body protested, and when inevitably you ran up against something you really couldn’t do, it felt like your fault. Like you’d failed somehow.

The acceleration was dizzyingly brutal: kept from doing anything for so long, now you were expected to do everything, and the goal wasn’t really to make you feel better. It was to achieve something as close to normalcy as possible, no matter how strenuously your weakened body protested, and when inevitably you ran up against something you really couldn’t do, it felt like your fault. Like you’d failed somehow.

And once those insurmountable roadblocks were found, the limits of your natural recovery defined—at least as far as the (misguided, but we’ll get to that) doctors were concerned—the next step certainly wasn’t acceptance. At a time when fighting to win at any cost—not just in the battle against polio, but in nearly every circumstance, great or small—was not only virtuous but expected, acceptance felt synonymous with giving up. Encouraging someone to come to terms with their disability was unthinkable: if the patients didn’t feel adequately distressed about how they were doing, what reason would they have to keep struggling?

The next step, instead, was surgery. Surgery to fuse bones, to transplant tendons from functional muscles to paralyzed ones, to shave down joints unhinged by muscle cramps. Dozens of surgeries, sometimes, stretched out over years, trying to account for growth, and the pernicious influence of time. For the most part, these procedures were designed not to make the patient feel more comfortable, but to make her more conventionally functional, closer to “normal”—whether or not that was something she actually wanted, or that her weakened body could support.

Lest you think I’m being hyperbolic, or exaggerating the extent to which recovery alone restored legitimacy, I want to share some excerpts from a March of Dimes pamphlet meant to “help” affected teenagers cope with the aftermath of their illness. There’s no date that I saw on this slender, seemingly innocuous document, but I’d bet anything it came from the mid-40s, with both fear and determination at their most histrionic peak.

“Everyone has problems to solve. Some are easy. Some are hard,” it begins, with an understatment that feels almost deadpan. “When you are ill your problems are more difficult to solve, more annoying, and many times you do not know where to turn for help.”

Then the language turns from merely patronizing to aggressively fraught with expectation: “it is…the function of the National Foundation to help you win your way back to health.” You and your family are “fighting to defeat the effects of the polio virus insofar as human skill and knowledge can do so”—and human skill and knowledge were held in high esteem at the time, with the country deep in the throes of new American exceptionalism, awestruck by unfathomable advances like the atomic bomb.

“If this little book does help you to ‘learn the score,’” the introduction concludes, “if it helps you become better able to conquer your polio and return to a full and happy life, it will have done everything we hoped it would do.”

There is no space, in that tone of enforced cheerfulness (which continues, blithely, through the rest of the booklet), for anyone whose recovery is less than triumphant. There are only winners and losers, without space left to to carve out a life in between—when life in between was most often the reality you confronted. No doctor ever asked a child when enough was enough, or how she felt about what was happening to her. They certainly never asked the darkest, and perhaps most crucial, question: Do you even want to get better?

It seems like an absurd thing to ask, doesn’t it? Of course you’d want to get better. There was nothing redeeming, hardly even anything tolerable, about this illegitimized existence, lost in the darkness of constant discomfort, at the mercy of a system you didn’t understand. But what the doctors failed to understand was this: rehab felt like a kind of limbo, a probationary period, where the rules and privileges of normal life were suspended. It was the place where you stayed while you waited to find out if your sentence would be commuted, and as long as you were there, everything else seemed far away. More often than not, the “real world” these kids were supposed to be fighting to rejoin seemed like nothing but a cruelly impossible dream.

It’s hard to convince yourself to work toward a goal with such a narrow definition. A difficult but attainable challenge is motivating. But it’s hard to imagine enduring that sense of futility, day in and day out. Lying in bed able to move just an arm, or a couple of toes, knowing that walking, that better, that normal, was the goal, made every incremental victory along the way seem less a triumph than an unbearable reminder of you how far you had to go.