Tags

Let me say this straight out: polio is not an easy thing to write about. Not an easy thing to characterize, anyway, without distorting it, without allowing some kind of bias to creep in. And in saying that, I join a long tradition of skewed perspective: it is impossible to paint a clear-cut picture of polio because such a thing doesn’t exist. Sixty or seventy years ago, a thousand questions went just barely unspoken in millions of households across the country: how dangerous was the disease, really? How likely was it to disable you permanently if you caught it? Who was most vulnerable—rich, poor, black, white, girl, boy? How many communities would it strike? Would it strike me, here, today?

If knowledge is power, they were grasping at straws. In some years there were 20,000 diagnosed cases; in others, three times that. Sometimes an individual outbreak paralyzed only one in a hundred victims; other times, one in two. Adults were more likely to end up devastated, but children caught the disease in greater numbers. Cancer killed many more people each year than polio, but polio did cause 22% of all physical disabilities among New York City’s children in 1944, and most of the other causes were congenital, inborn. Epidemics began like clockwork in mid-June, rumbled inexorably toward August, and faded to murmurs by late September, and we still aren’t entirely sure why.

If you believed the March of Dimes’ alarmist public service announcements, and took the tragic, lovely poster children who smiled from shop windows to heart, you were probably too terrified to ever leave your house. Affronted doctors worked constantly to counter newspaper coverage that reported casualties in offset boxes like sports scores, tired of calming parents who believed a diagnosis presaged certain death, and if you believed them you probably weren’t worried enough. The approach modern commentators tend to take runs something along the lines of, “Well, the public probably percieved polio as a greater threat than it actually was, both because it was so frightening, and because the media coverage of it was so extensive.” Which is true. But it’s nothing like a conclusion, nothing like information, nothing like clarity.

If the story of polio is anything, it’s a tale about the ways in which perception transforms into reality.

But it’s also science, of course, and science is objective and explainable—at least, we like to think it is. The world is unpredictable, and things we like to think of as absolute are too often contingent on variables beyond our control. There are so many different presentations of the virus, so many possible “clinical syndromes,” that an early medical text proposed eight or nine different “types” of polio-related illness; all were drastically distinct, and at least half potentially fatal.

This, at least, is true: polio is caused by a virus, the uncreatively named “poliovirus,” part of the same family as the viruses that cause most stomach upsets and a half-dozen different kinds of common cold. The word itself is a little bit bizarre: squat, and kind of ugly, and if you don’t know its Greek root, meaningless. A shortened form of poliomyelitis, I’m not sure knowing what it means makes things a whole lot better: polios is Greek for “gray,” and a myelitis is inflammation of the sheaths that protect the nerves of the brain and spinal cord. And they did mean “gray brain swelling” literally: it was merely a blunt description of the damage done to the nervous systems of those who died from the disease. Their nerve tissue would be drained of color on autopsy, faded to grayscale from its normal healthy pink.

The gray death. It doesn’t have quite the same ring to it as bubonic plague, but if you found yourself in its path it was every bit as terrifying.

Viral infections propagate in several ways, but the most common, the one that the poliovirus uses, is especially brutal and crude: once the virus enters one of the body’s cells, it replaces the genetic material that carries the cell’s “instructions” with its own. Rather than producing the proteins that keep us alive and healthy, the cell begins to churn out endless copies of the virus. Unlike the proteins, these new viruses have no way to escape the cell, and the membrane swells until it bursts. Too devastated to repair itself, the cell dies, and uncountable new viruses flood the surrounding tissues, looking for new cells to colonize, so the cycle can begin again. (There is a particularly good illustration of this the National Museum of American History web site.)

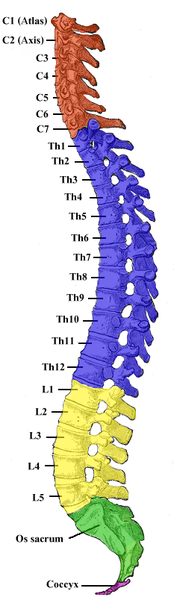

When this happens in the initial stage of the infection, when the invasion is “systemic”—distributed throughout the body, replicating mainly in the stomach—this is unpleasant, but not especially devastating. The vast majority of the body is more than capable of regenerating, after the immune system kicks into gear, and a few long days of misery come to an end. It’s when the infection burrows deeper that the stereotypical paralysis occurs: once it breaches the nervous system, the poliovirus has a particular, peculiar affinity for the nerve cells known as the “anterior horn cells” of the spinal cord. These cells form the chain reaching from the brain, where the impulse to move originates, down the spine to the muscles, where the contraction itself occurs. And with each cellular “lysis,” those connections grow weaker and weaker, until the line finally, agonizingly, goes dead.

We move more than we realize. As I’ve been sitting here, I’ve readjusted in my chair a half-dozen times, crossing and uncrossing my legs, boosting myself up to tuck them underneath me. When I’m at a loss for words, I crack my knuckles, wiggle my toes, push my hair obsessively behind my ears and then ruffle it free again. During one particular stuck moment I got up for a quick set of jumping jacks. Even typing requires a spectacular coordination, and when I think too hard about how it happens my fingers stumble on the keys. It’s almost surreal to think that these things we do so thoughtlessly, these incredible fluid movements, originate as nothing more than electric shocks, racing through our bodies at literal lightning speed. But that’s exactly what they do.

Muscles are dumb. I’ll talk far more about them later, when I discuss physical therapy in more detail, but they just aren’t terribly ambitious: the only thing an individual muscle fiber knows how to do is contract. It doesn’t even know anything about relaxing, not really: it’s either on, and squeezing, or it isn’t. And somehow these many thousands of binary decisions, distributed throughout the six hundred and fifty muscles that string us together, make possible the incredible feats of dexterity we think nothing of every single day. I could talk about ballet dancers and sculptors and ultramarathon runners. But I prefer to think of the astonishing complexity of small things: cooking breakfast. Writing by hand. Putting on shoes. Getting in and out of chairs. Pushing up on tiptoe to reach that thing on the top shelf.

It’s those things you miss the most when they’re gone.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

As I alluded earlier, polio is on the most basic level a stomach virus. It’s where the infection usually originates, and it’s where the infection in most cases stays. “Abortive” polio, it’s now called, and it isn’t any fun—the sore throat is wicked and the nausea can be debilitating—but if that’s the extent of the infection, after a couple of days you’d be in the clear. (Most of the time, anyway: in some cases, the symptoms disappear for a few days in a kind of “dormant” period, before returning again with much greater ferocity. Polio narratives are thick with these kinds of frightening uncertainties, and the sense that no one was ever quite entirely safe.)

The next possible manifestation of the disease, for those not fortunate enough to recover right away, is called simply “nonparalytic polio.” It’s more properly a meningitis, which most people have heard something of: an inflammation of the lining that covers, and under most circumstances protects, the brain and spinal cord. It’s a different kind of infection from the bacterial meningitis that sometimes makes the news, but it’s still extremely uncomfortable and potentially very dangerous. The compression on the nervous system causes extreme sensitivity to light and sound, and dramatic stiffness of the neck and back, with a headache so severe and sudden it’s sometimes described as a “thunderclap.” But as long as the poliovirus stays around the nervous system and not inside it, when the fever breaks and the pain subsides, the exhausted rigidity vanishes with it.

The next possible manifestation of the disease, for those not fortunate enough to recover right away, is called simply “nonparalytic polio.” It’s more properly a meningitis, which most people have heard something of: an inflammation of the lining that covers, and under most circumstances protects, the brain and spinal cord. It’s a different kind of infection from the bacterial meningitis that sometimes makes the news, but it’s still extremely uncomfortable and potentially very dangerous. The compression on the nervous system causes extreme sensitivity to light and sound, and dramatic stiffness of the neck and back, with a headache so severe and sudden it’s sometimes described as a “thunderclap.” But as long as the poliovirus stays around the nervous system and not inside it, when the fever breaks and the pain subsides, the exhausted rigidity vanishes with it.

In anywhere from five to fifty percent of cases—the three different “strains” of the virus varied greatly in severity, as did the accuracy of case reporting—the infection keeps pushing deeper, until it breaches the tender innermost spaces. Stereotypically, the virus spreads through the nervous system in an “ascending paralysis”: entering at or near the base of the spinal cord, the virus climbs that chain of cells, spidering its way back up towards the brain, ravaging the cells it commandeers in the process. The body is wired more or less from the bottom up, too, so that so-called “milder” paralytic infections, choked off quickly by a panicked immune system, leave behind the leg weakness typically associated with the disease.

As the damage rises, the difficulties become more sweeping and severe: about halfway

up the back sitting becomes a struggle. A little higher, and moving the arms is all but impossible. As the infection pushes into the uppermost segment of the spine, the cervical spine that flexes in the neck, breathing is suppressed; that’s the area wired to the diaphragm, which controls the inflation of the lungs, and just above the rib muscles that expand and contract to make room for them.

In what is arguably the most extreme form of the illness, it creeps all the way up to the base of the brain itself (“bulbar polio,” referring to an archaic term for the brainstem), which controls everything we do without thinking about it. It keeps our hearts beating. It keeps us from forgetting to breathe. It sends the signals we need to digest food properly, and governs reflexes like the one we use to swallow it. It controls our body temperature and our sleep. And it can be torn apart as surely as the motor neurons.

The fallout from that, as you can imagine, is devastating.

I tell you these things because it’s important to understand the mechanical assault, to fully grasp the firestorm happening inside patients’ bodies. It’s important to understand because these facts form the basis for the incredibly contentious debate that erupted over the best practices in physical therapy for polio. I tell you because I want you to know what we’re dealing with, and the magnitude of the physiological destruction it wrought.

But understand this, too: we didn’t even know most of these things for sure, back in the forties and fifties, when this terror opened up communities like it was ripping out a seam, warping the pattern of everyday life, exposing the fragile, private lining from which we tried so hard to avert our eyes. It was a time when the departments of neurology and psychology could be headed up by the same person, before accurate conduction studies to map beleaguered nervous systems, before the electron microscope let us see our enemy up close. (The poliovirus was first imaged in the early 1950s.) When we were so desperate not to acknowledge our helplessness in the face of this wayward force of mother nature that we injected patients with paralytic poisons and the blood of other victims in an attempt to arrest the progress of the disease. It was not a time when logic, as we understand it now, ruled the day.

But understand this, too: we didn’t even know most of these things for sure, back in the forties and fifties, when this terror opened up communities like it was ripping out a seam, warping the pattern of everyday life, exposing the fragile, private lining from which we tried so hard to avert our eyes. It was a time when the departments of neurology and psychology could be headed up by the same person, before accurate conduction studies to map beleaguered nervous systems, before the electron microscope let us see our enemy up close. (The poliovirus was first imaged in the early 1950s.) When we were so desperate not to acknowledge our helplessness in the face of this wayward force of mother nature that we injected patients with paralytic poisons and the blood of other victims in an attempt to arrest the progress of the disease. It was not a time when logic, as we understand it now, ruled the day.

These patients—these kids, mostly—didn’t care what was going on in the deepest reaches of their cells. It’s disingenuous to say that we shouldn’t either—that’s why I told you all about it. But it tells us nothing about the things that really matter: the brutal contagion of fear, the stigma and terror of isolation, the pain and the stares and the shame. The details are interesting mainly in that they are so brutally indifferent, and we are so much at their mercy. The details are almost insulting.

What polio was is a notion utterly divorced from what polio was like.

And now that we’ve covered the basics, it’s time to delve a little deeper.