Tags

What scares you more: the thing you don’t see coming, or the one you can’t escape?

I guess you can learn a lot about a person from how they answer that question. I’ve been staring at it for days, and I don’t know if I could tell you where I fall—especially if we’re asking not as a horror movie audition, where that verdict is the end of the story either way, but as something both subtler and more awful, where the choice is only its beginning.

Polio isn’t loud, at least not at first, not the way I think we wanted it to be. The way people must have imagined it was, in a world constantly haunted by propaganda that managed to feel defeatist even as it pledged to do the conquering. The March of Dimes—which I realize I’ve mentioned several times without any real explanation, but trust me, before long you’ll know more than you ever hoped for—waged a ferocious war against it for twenty long years, drafting a huge swath of the nation’s mothers into the fight, and when you go into battle, you like to imagine you know the enemy. You want something ugly to point at, to hate, something as obviously repulsive as the villainous offenses themselves.

In the end, the brutal truth of polio is that the answer to the question doesn’t matter. It didn’t differentiate, one way or the other; more often than not, its victims confronted both. The metal temples to its sinister domination, the iron lungs and braces like birdcages, became the symbols we raged against. But the reality of the experience itself was often a much quieter, sadder undermining—and hardly anyone ever knew when to steel for the impact.

It was an ordinary day. Or it was an extraordinary one, but you remember it as ordinary, eerily so, in the same way that, when you ask someone to tell you about a landmark catastrophe, something like September 11th, they so often talk first about the weather. It was such a beautiful day.

A day marked not with searing agony or sudden weakness—not usually, at any rate—but with something more insidious: a missed step, a stubbed toe. A late-spring school day spent with your head on your desk, the sound of your classmates’ pencils on test papers suddenly unbearable, your own exam still untouched in front of you. A blank space in a conversation, a sudden gaping where there should have been easy words.

Your stomach hurt. Your head hurt even more. Trembling chills canceled out the summer sun, and your throat was so sore it hurt to talk. Those first few days were miserable, in a way I think we’ve all endured at one time or another: thoughts furred with fever, aching all over, too tired to move except during sleepless nights spent running back and forth to the bathroom. Icky. Exhausting. But not the stuff of brimstone nightmares.

Your stomach hurt. Your head hurt even more. Trembling chills canceled out the summer sun, and your throat was so sore it hurt to talk. Those first few days were miserable, in a way I think we’ve all endured at one time or another: thoughts furred with fever, aching all over, too tired to move except during sleepless nights spent running back and forth to the bathroom. Icky. Exhausting. But not the stuff of brimstone nightmares.

For all the hype about polio, unless you lived in the midst of a raging epidemic, at first the possibility occurred to almost no one. The same mothers who forced children to touch chin to chest every time they came home from the playground, checking for the hallmark neck stiffness, sent their sick kids to bed with nothing but a couple of aspirin, and maybe a hot-water bottle to soothe slender, aching limbs. Maybe it was self-defense. Maybe it was just ignorance—ignorance to the real threat, subsumed by its distorted public image. In the anxiety-ridden, war-torn first half of the twentieth century, you quite literally had to pick your battles, and every single tummy ache couldn’t trigger a full-on lockdown.

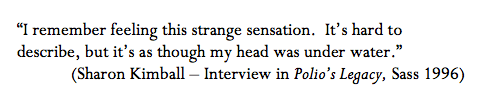

But however innocuous it looked on the surface, from the very beginning something was different. There’s no one thing people can point to, asked to recall exactly why they felt so awful, but even in its early stages polio was something to be suffered, rather than merely waited out. Everything about it threw the world off-balance: the overwhelming nausea, the disproportionate vertigo that made the ground seem to sway, the pricking pins and needles turning touch to sandpaper—intermittently now, and, as the illness progressed, in great drenching waves of skin-crawling sensation.

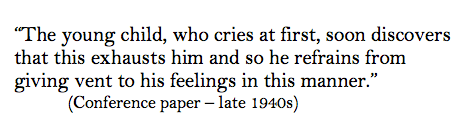

Children wept. Adults wept, too, sometimes, or else they turned tense and irritable, hypervigilant with anxiety. It’s possible the emotional sensitivity came of the viral scouting parties already mapping out territory in the brain, or it could have been something else; we probably won’t ever know for sure. But the disease was such a profound misery that medical manuals often listed “inconsolable” behavior as a genuine symptom, one that contributed significantly to the likelihood of a positive diagnosis.

Sometimes it got better. Sometimes the fever broke, and stability returned, the nagging sense of the world viewed through a warped pane of glass dissipating overnight. For the most part, those people never knew there had been anything so seriously wrong with them at all. Never knew just how close they’d been to the kind of precipice that dissolves beneath your feet. They blamed bad food at a barbeque, or that night they went to bed with hair still wet. And then they carried on with their lives, the lucky ones.

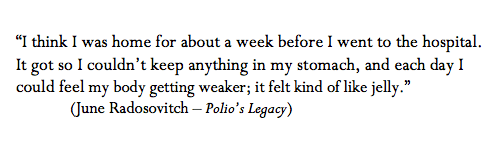

But maybe you weren’t so lucky. Maybe the headache that had merely nagged for days turned blinding, molten metal pouring down the nape of your neck until your whole spine was stiff as iron. Maybe you hadn’t been able to keep anything down all weekend, and suddenly found you couldn’t even swallow the water in the glass you so unsteadily held. Maybe the soreness in your calves, a strain that used to feel just like adolescent growing pains, turned overnight to cramps so bad they made you cry.

And the parent or partner to whom you’d confessed darted off to call the doctor, and left you to sit with the spark of terror you’d watched kindle in their eyes.

This was the moment of truth: the collision of your world with the hellish one you heard on the radio and saw in movie-theatre public service announcements, the one the media constructed to evoke pity and fear in equal measure. There were so many things you should have suspected, but didn’t, precautions you ought to have taken, signs you should have seen. Adrenaline made your stomach drop, this time, rather than nausea: what was going to happen now, if it was true? Had you gotten somebody else sick? What would become of your brothers and sisters, your parents, your kids?

What would become of you?

With very few exceptions, the doctor took one look—at the ginger way you held your body, how you winced at bright light, the limp as you walked or the unnaturally exaggerated curve of your spine—and sent you straight to the ER.

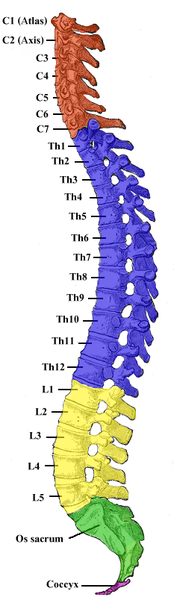

There you were met with either an overwhelming rush of activity or a long and interminable wait. During an epidemic, lines stretched for hours, and only those already struggling for breath were allowed to skip ahead; if you had the misfortune of being the first case in town that season, the entire establishment descended on you in one predatory blink. One way or the other, a single detail was constant: the forceful violation of the spinal tap, a single point of anguish to slice through the broad blur of misery. Confirming a diagnosis required a sample of spinal fluid, collected by curling a victim already painfully rigid into a fetal position, and then sliding a thick needle between two vertebrae until clear liquid trickled out.

There you were met with either an overwhelming rush of activity or a long and interminable wait. During an epidemic, lines stretched for hours, and only those already struggling for breath were allowed to skip ahead; if you had the misfortune of being the first case in town that season, the entire establishment descended on you in one predatory blink. One way or the other, a single detail was constant: the forceful violation of the spinal tap, a single point of anguish to slice through the broad blur of misery. Confirming a diagnosis required a sample of spinal fluid, collected by curling a victim already painfully rigid into a fetal position, and then sliding a thick needle between two vertebrae until clear liquid trickled out.

There was no anesthesia for this procedure; frequently there was no explanation for this procedure. You might never have found out why it was necessary. But you never, ever forgot it.

The instant the diagnosis was final, complete isolation began. Children and parents (and husbands and wives) were separated, often by force; neither knew when they might see the other again, or if it might be in a coffin.

So then there was silence, and you were alone.

The fuss of admission and diagnosis gave way to the heavy void of solitary isolation, or the eerie quiet of an open polio ward, filled with the labored breathing of a dozen others just as sick, and the palpable tension of their own unspoken fears. Still nauseous, still disoriented, likely still sore and headachy from the spinal tap, patients suddenly found themselves afflicted with something new: invisibility.

“I didn’t know what the hell was wrong with me,” Russell told me last week, fingers twisting together, gaze cast down to the kitchen table. Russell, my interviewee, who fell ill when he was fourteen, and talks about it like it happened a year ago, instead of seventy-three.

“They didn’t tell you?” I asked, incredulous.

“Oh, they could’ve,” he shrugged, without missing a beat. “But I probably didn’t understand what they were talking about.”

It’s a revealing thing to say: for all the paranoia surrounding the idea of the illness, hardly any of the kids it ensnared had any idea what it would look like if it assaulted them. Neighbors worse off than you were terrify ing, and wardmates in recovery, objects of seething, fevered envy; none of you had any idea what was going on. Doctors dismissed the notion that even adults or teenagers had the right or ability to dictate their own medical care. No one asked you what you wanted, what you needed, how you felt—or if you were okay with any of the many confusing, uncomfortable things they might be doing to you.

ing, and wardmates in recovery, objects of seething, fevered envy; none of you had any idea what was going on. Doctors dismissed the notion that even adults or teenagers had the right or ability to dictate their own medical care. No one asked you what you wanted, what you needed, how you felt—or if you were okay with any of the many confusing, uncomfortable things they might be doing to you.

“I had a temperature of 106 for ten days,” one girl says matter-of-factly, in a book of short interviews called Polio Voices. The brain is supposed to rebel against this sort of thing; the “thermostat” in the hypothalamus has this number set as its absolute upper limit, since at that point the risks start to outweigh the defensive benefits the body gets from running a fever. It’s not necessarily dangerous, intrinsically, but it tells us something about how completely beholden to the virus its victims became, once it infiltrated the nervous system. And once you were in the hospital, you couldn’t just go to the cabinet and pull down a couple of aspirin. You couldn’t get up to walk to the bathroom—either because you were too weak, or because you were under strict orders not to exert yourself. (It was thought—correctly, it seems—that any activity after the onset of spinal infection would worsen the ensuing paralysis.)

Things crop up in these stories over and over again that would be horrifying if they happened just once. The repetition gives them a kind of melancholy sadness, a strange, dark wonderment at the workings of this microcosmic world: just a cursory skim through the reminiscences in the books I’ve collected turned up three people who had overheard someone saying that they’d died. To lie there in the dark, unable to wrestle away a sheet pulled up too high, lightheaded, breathing so shallowly the doctors apparently didn’t notice—the patients knew they were alive. Maybe. But everything about the illness was so surreal it’s hard to believe they were sure.

Things crop up in these stories over and over again that would be horrifying if they happened just once. The repetition gives them a kind of melancholy sadness, a strange, dark wonderment at the workings of this microcosmic world: just a cursory skim through the reminiscences in the books I’ve collected turned up three people who had overheard someone saying that they’d died. To lie there in the dark, unable to wrestle away a sheet pulled up too high, lightheaded, breathing so shallowly the doctors apparently didn’t notice—the patients knew they were alive. Maybe. But everything about the illness was so surreal it’s hard to believe they were sure.

It felt like the world was ending, every illusion of comfort and safety shattered in a single sledgehammer blow, and you had nothing to do but sit at the window watching shards of clinging glass drip down one by one, and wonder what manner of demon would climb through the gap next. And that dark inner world felt impossibly strange, pressed up against the bustling, well-lit one you lived in, where doctors hurried from one bed to the next saying words even adults didn’t understand, and except in the most horrible extremity the nurse showed up at the same times every day to give you juice and take your temperature. The whole universe had gone mad, but except for the occasional shrieking outbursts of a roommate unable to cope or some poor soul down the hall, it wasn’t a derangement with any external confirmation.

The roiling sea—the riptides of fear, your churning stomach, the uncertainty of rescue and the Kraken lurking always just beneath the waves—was contained entirely inside you. And who were you, so clueless, so sick, so unstable, to say if any of it was even real? The doctors seemed indifferent, when they even noticed or remembered you were there. Your body was betraying you, this shell you’d so thoughtlessly relied on in homeroom and games of kickball, at work and in the bedroom, and so why should you believe the blinding agony it felt? Maybe the problem was just your delirium. Maybe you were the problem. Who was left that you could trust?

So you did your best to stay quiet and composed, to be brave and not make a fuss, while sweat-crusted sheets rubbed your tender body raw. The oceans of salt, at least, those were real: polio brings on drenching sweats—“diaphoresis,” in doctor-speak—out of proportion even to the fever.

And you waited. Floating.

The brain is precious, and the body knows it. Dying nerves—nerves dying, as I said in the last post, stretched and popping like overinflated balloons—don’t go quietly. As the static on the line between the muscles and the brain grows louder, the illness shifts from a vague, squirming discomfort to a fierce and violent possession. Muscle cramps far too powerful to stretch out lasted for days, so persistent that frequently they didn’t relax even after the fever broke. A sensory condition called hyperaesthesia, in which normal sensations feel exaggerated and sometimes painful, made the pressure of the bedsheets so unbearable metal frames were used to keep them from touching patients. Spasms and tremors shivered through burning-hot bodies, sometimes confined to an unsteady hand, other times triggering whole-body shocks like the ones that sometimes happen as you’re drifting off to sleep.

Leaving you at the mercy of a torturer you could neither see nor explain. There was no wound to point at, no captor to loathe. No amount of struggle made it any better; mental effort was exhausting, and most physical treatments just made the pain worse. In many ways, this is far more terrifying than the notion of a sudden, sweeping paralysis: a body’s refusal to cooperate is scary—and sometimes infuriating—but not nearly as much so as being betrayed by it, backstabbed so primitively by something you couldn’t escape.

The specter of mortality was unrelenting, with silent bodies carried out through rooms still quietly full of life, and dire prognoses issued loudly at bedsides, as if their occupants were already too far gone to hear. The constant humming wheeze of the iron lungs carried with it a very particular ambiguity: for a child feeling breathless in the dark—fatigued by dehydration, weak with creeping spinal infection—just the sight of the machine was a tremendous relief. But if you went into that hulking contraption, would you ever come out again? Most people did, after a few days or weeks of rest, letting the pressurized chamber do the work that tired breathing muscles couldn’t. But some would stay there for the rest of their lives. And lying there, growing weaker by the hour, exhausted and sometimes delirious, how could you possibly think about anything else?

The specter of mortality was unrelenting, with silent bodies carried out through rooms still quietly full of life, and dire prognoses issued loudly at bedsides, as if their occupants were already too far gone to hear. The constant humming wheeze of the iron lungs carried with it a very particular ambiguity: for a child feeling breathless in the dark—fatigued by dehydration, weak with creeping spinal infection—just the sight of the machine was a tremendous relief. But if you went into that hulking contraption, would you ever come out again? Most people did, after a few days or weeks of rest, letting the pressurized chamber do the work that tired breathing muscles couldn’t. But some would stay there for the rest of their lives. And lying there, growing weaker by the hour, exhausted and sometimes delirious, how could you possibly think about anything else?

The iron lung was the most famous intervention, but it was hardly the only one—and in many ways it was the least extreme. Something called “convalescent serum” was crafted from the blood of polio survivors, on the premise that their antibodies would bolster the response of the immune system currently under assault. Curare, an extremely potent poison, causes paralysis with a rapidity the poliovirus can only envy; the sick were sometimes put on ventilators and injected with the toxin, in case total motionlessness could slow the viral spread. Vitamin injections irritated overtaxed bodies, and often did more harm than good.

All that’s just the medicine, though; the physical regimen was equally dramatic. Some patients were immobilized in splints to keep them still, restrained like the mental patients they might have begun to empathize with, while shuddering involuntary movements swept through their bodies. Others were bundled into steaming wool compresses and wrapped in rubber sheeting to relax their spastic muscles; this was one of the only effective interventions, but it must have been hard to believe it was doing any good, when the fever was so high they had to alternate heat therapy with rubdowns of ice. The single most lifesaving revelation in the treatment of bulbar—brainstem—polio was the practice of tilting patients’ beds so their heads were inclined towards the ground, lower than the rest of their bodies. Not because this made it any easier to breathe (that role, for those patients, was played by “rocking” beds, whose mechanized swing back and forth coerced the diaphragm into something like a normal pattern of expansion and contraction). Because those patients often lacked the reflex power to swallow their own saliva, and letting it drain down their chins kept them from fatally choking.

All that’s just the medicine, though; the physical regimen was equally dramatic. Some patients were immobilized in splints to keep them still, restrained like the mental patients they might have begun to empathize with, while shuddering involuntary movements swept through their bodies. Others were bundled into steaming wool compresses and wrapped in rubber sheeting to relax their spastic muscles; this was one of the only effective interventions, but it must have been hard to believe it was doing any good, when the fever was so high they had to alternate heat therapy with rubdowns of ice. The single most lifesaving revelation in the treatment of bulbar—brainstem—polio was the practice of tilting patients’ beds so their heads were inclined towards the ground, lower than the rest of their bodies. Not because this made it any easier to breathe (that role, for those patients, was played by “rocking” beds, whose mechanized swing back and forth coerced the diaphragm into something like a normal pattern of expansion and contraction). Because those patients often lacked the reflex power to swallow their own saliva, and letting it drain down their chins kept them from fatally choking.

In this firestorm of painful detail, I’ve lost the thread of the story I was telling. Misplaced that anonymous person on that curiously beautiful day, the one sent so unceremoniously out to sea. And maybe I’m making excuses for my own labyrinthine writing, my struggle to wring coherence out of this huge and elusive topic, but it feels appropriate, somehow. All this skipping around is fitting: losing threads and finding them again, later, when the context has changed, and they seem to mean something else. Being in this situation was a constant exercise in triangulation, struggling to figure out where you were—mentally, medically, spatially—and what the hell that meant. Losing yourself, over and over again, and repeatedly rediscovering a person not quite the same as the one you’d left behind.

In this firestorm of painful detail, I’ve lost the thread of the story I was telling. Misplaced that anonymous person on that curiously beautiful day, the one sent so unceremoniously out to sea. And maybe I’m making excuses for my own labyrinthine writing, my struggle to wring coherence out of this huge and elusive topic, but it feels appropriate, somehow. All this skipping around is fitting: losing threads and finding them again, later, when the context has changed, and they seem to mean something else. Being in this situation was a constant exercise in triangulation, struggling to figure out where you were—mentally, medically, spatially—and what the hell that meant. Losing yourself, over and over again, and repeatedly rediscovering a person not quite the same as the one you’d left behind.

That was the person you’d have to carry back into the world with you, when all this was over. Being sick with polio was awful. But the acute illness was a thing with boundaries, a fever dream with a beginning and an end. You woke up one day—a week into the trial, or maybe two or three—with sheets even more thoroughly soaked through than usual, and the sun was a little brighter, and your head a little clearer. Gravity had tripled, and your body felt sore and reluctant, in the places that it worked at all. The fever had broken, and a line had been crossed. For some the moment came as a tremendous relief; for others, that first self-check felt more like a sentence handed down after a long, squeamish deliberation. Maybe you’d be sent home, after a few weeks of recuperation, or maybe you’d be entering the scary, uncertain world of inpatient rehabilitation, but either way, one thing was true. You no longer had polio. You were a survivor.

And that was a thing that you never woke up from.